Many small nonprofits find themselves in a familiar position: minimal staff, a supportive but cautious board, limited systems, and no established donor base. Grants haven’t materialized. Marketing budgets don’t exist. And every proposed investment feels risky. If this sounds familiar, you’re not behind. You’re in the earliest and most important phase of building fundraising infrastructure. When you’re starting from zero, the goal is not to launch sophisticated campaigns. The goal is to build a stable foundation. Here’s what that actually looks like.

In an era where digital platforms shape visibility, fundraising, and public narrative, many nonprofits have come to rely heavily on social media. It’s fast, accessible, and often effective. Until it isn’t. Recent events across the sector serve as a reminder of a critical truth nonprofit leaders cannot afford to ignore: social media is rented space, not owned infrastructure.

This post is written for board members navigating a difficult reality: when the board chair’s behavior is actively harming the organization.

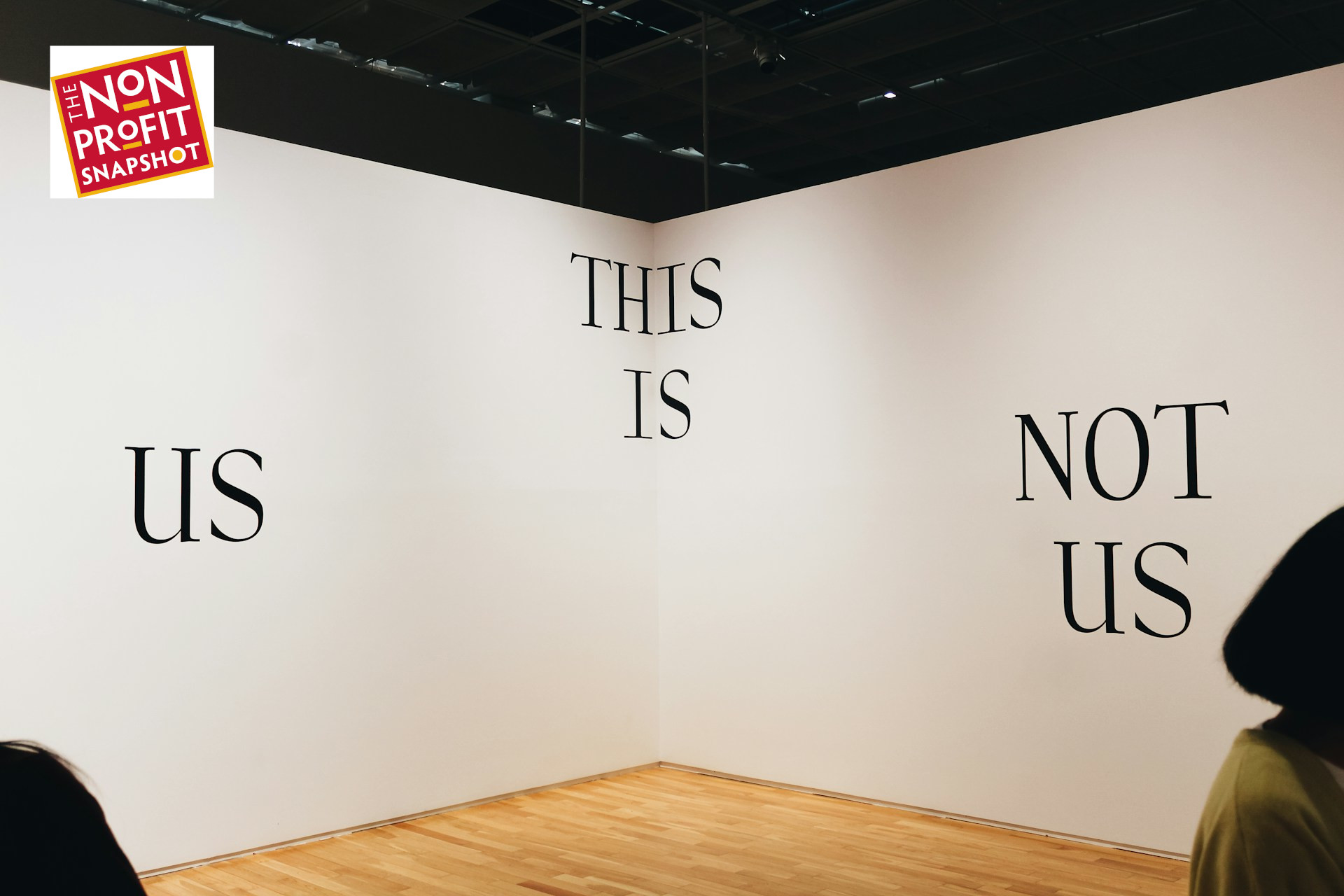

Nonprofits play a critical role in a healthy democracy, but they must do so ethically, legally, and in alignment with their missions, especially given 501(c)(3) restrictions. Combating authoritarianism and fascism is not about partisan politics; it is about protecting democratic norms, human dignity, and community resilience.

Persistent myths about how grants actually work continue to undermine even strong nonprofit organizations. In a time of constrained funding, heightened competition, and increased scrutiny from funders, relying on outdated assumptions can cost nonprofits both time and credibility. Let’s unpack six common grant writing myths, and what nonprofit leaders should understand instead.

Nonprofit mergers are increasingly being explored as a strategic path toward greater impact, stability, and sustainability. When done right, a merger can strengthen services, expand reach, and create operational efficiencies that benefit communities, donors, and stakeholders alike. But the process isn’t simple. Mergers require clarity, care, and thoughtful planning. Below is a practical roadmap to guide nonprofit leaders through a successful merger.